We studied the participles for all the tree tenses, but as for the ordinary past tense, we did study it only in case of the future tense. Now let us look at ordinary or regular verbs in the past tense. Few of the examples of these sorts of verbs are given through the sentences below:

The word in italics is the verb.

I went.

You restrained.

We stood.

Obviously, these sentences can be easily translated to the Sanskrit language, but in a rush to do so, let us not neglect a few factors. We need to understand that in Sanskrit, past tense has three different versions. The first one is recent past, the second one is not so distant past and the third one is distant past.

However, we have to study just the ordinary past, but for that, we need to understand what exactly is the ordinary past, ordinary past is the not-so-distant past, this is because the recent past and the distant past are highly complicated. It is for this reason that “not-so-recent” past has been called the ordinary past. Now we shall look at the example given below, and what happens when the sentences above are converted to the ordinary past tense.

अगच्छम्

agaccham

I went

अयच्छः

ayachah

You restrained

अतिष्ठाम

Atisthama

We stood.

Please note: As far as the past participle is concerned, it can be used in all three of the examples of the ordinary past tense.

Example: Gata.

Endings in the past tense:

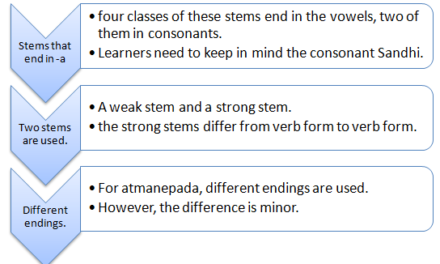

There are three types of endings, P endings, A endings for the simple verbs and A endings for complex verbs. However, before we deal with endings, let us learn some more about the vowel\sound in all the above-mentioned verbs.

This vowel is attached to the verb as a mark of the fact that the stem formed belongs to ordinary past tense. This sound is attached to a regular stem in order to produce a unique “past stem”. It is for this reason that the “a” sound in a verb in Sanskrit is not hidden. This can be explained with the diagram given below:

इष्

is.

want (root)

इच्छ

iccha.

want (present tense)

ऐच्छ

aiccha.

wanted (ordinary past tense)

It can be noticed that a is added to a word that already has a vowel (that is, i), now that a is added to a pre-existing vowel, it will become strong vowel.

Now let us look at the endings in past tense. Even though, they are similar to the present tense, there are a few differences. Initially, we shall look at verbs with P endings and then proceed on to the ones with A endings. The table below shows the ordinary past tense with P endings. The word taken is Bhu.

| Singular | Plural | Dual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third person | abhavat | abhavan |

|

| Second person | abhavaḥ | ||

| First person | abhavam | abhavāva | abhavāma |

For the sake of comparison, let us also look at endings as far as present tense is concerned. We shall take the same example, this time around as well.

| Singular | Plural | Dual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third person | bhavati | bhavanti |

|

| Second person | bhavasi | ||

| First person | bhavāmi | bhavāvaḥ | bhavāmaḥ |

What can be noted is that when words are transformed from present tense to the past tense, the last letters are lost.

Now let us take a look at the complex verb classes, they have the same ending, however, all the verbs in the first singular make use of the strong stem. Look at the table given below to understand the same further. (Verbs which are in the strong form are given in Italics.)

| Singular | Plural | Dual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third person | asunot | asunvan |

|

| Second person | asunoḥ | ||

| First person | asunavam | asunuva | asusuma |

Now we shall look at A endings in case of ordinary past tense and past tense. The table given below looks at ordinary past tense with A endings. The example used in this case is labh.

| Singular | Plural | Dual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third person | alabhata | alabhanta |

|

| Second person | alabhathāḥ | ||

| First person | alabhe | alabhāvahi | alabhāmahi |

Note: the formation of complex words is done in almost the same manner. Look at the table given below to understand the A endings and their application in past tense.

| Singular | Plural | Dual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Third person | असुनुत, asunuta | असुन्वत, asunvata |

|

| Second person | असुनुथाः, asunuthāḥ | ||

| First person | असुन्वि, asunvi | असुनुवहि, asunuvahi | असुनुमहि, asunumahi |

Look at the two examples given below.

Amahi becomes mahi, avahi becomes vahi.

Also note that nta becomes ata, (for this, refer to the diagram in the previous chapter).

It is also noticeable that the differences within these are parallel to the differences within Atmanepada.

Now we have to deal with verbs and prefixes. The rationale that we will keep in mind is that initially, prefixes used to be separated from the verb, and then they started being attached word primarily, now the sound “a” can be found in the middle of the verb. Look at the example given below to understand this further.

Pragatigam-pradatgachati

Pratigam-pratyagachat

Note how the sound a has been locked in the middle of the word